The Indian right-wing media has enthusiastically covered the news of the hijab ban in Tajikistan. It was stressed that a 99% Muslim-majority country has banned the hijab. They also explore different angles of the story. We understand their intentions in highlighting such news, but they should also analyze the historical context behind such events in Central Asian countries. They must recognize that these Muslim populations have survived severe persecution under the USSR and Russian imperialism. Despite this, they have remained steadfast in their beliefs and continue to fight for their right to practice their religion. It is essential to understand this historical perspective, and that is what we discuss today.

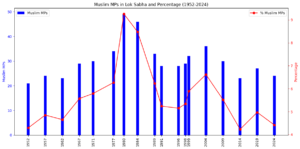

The history of Central Asia under Soviet rule is marked by significant oppression and systematic suppression of Muslim communities. Various peoples and tribes of the Muslim faith, including the Tatars, Bashkirs, Turkomans, Kazakhs, and Uzbeks, populated and continue to inhabit vast stretches of southeastern Russia and Central Asia. Despite their diverse languages and dialects, these groups were and still are united in spirit by their adherence to Islam. Prior to Soviet control, they numbered almost 30 million. Which now has a population of approximately 72 million which includes Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan recognized as Muslim-majority countries. We want to highlight the chronology of the persecution of the communist regime which claimed to bring an egalitarian society to the world.

- Initial Conquest and Suppression

The Russian conquest of Central Asia began in the 19th century and culminated in the early 20th century with the full integration of the region into the Russian Empire. The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent establishment of the Soviet Union brought about profound changes and challenges for the Muslim populations of Central Asia. The Soviet regime viewed religion as an obstacle to its Marxist-Leninist ideology, which promoted atheism and sought to eradicate religious beliefs and practices.

One of the first measures taken by the Soviet authorities was the confiscation of waqf properties. Waqf properties, which were endowed for religious or charitable purposes, played a crucial role in sustaining Islamic educational and religious institutions. Their confiscation deprived the Muslim communities of their economic base and significantly weakened their religious infrastructure.

- Anti-Religious Campaigns

The Soviet regime launched a series of anti-religious campaigns aimed at eliminating Islam from public and private life. These campaigns were characterized by the closure of mosques, the banning of religious education, and the persecution of religious leaders. Thousands of mosques were closed or repurposed for secular uses, such as warehouses or cultural centers. The few mosques that remained open were closely monitored by the state.

Religious education, which had been a cornerstone of Islamic life in Central Asia, was severely curtailed. Madrasas were shut down, and religious instruction was prohibited. The Soviet authorities replaced traditional Islamic education with state-controlled secular education, which promoted atheism and Marxist-Leninist ideology. Children were taught to reject religious beliefs and to embrace the principles of scientific atheism.

- Persecution of Religious Leaders

The persecution of religious leaders was a central aspect of the Soviet campaign against Islam. Imams, scholars, and other religious figures were targeted for arrest, imprisonment, and execution. Many were accused of being counter-revolutionaries or enemies of the state. The loss of these religious leaders dealt a severe blow to the Muslim communities, as they were deprived of their spiritual and moral guidance.

The purges of the 1930s, orchestrated by Joseph Stalin, were particularly brutal. Thousands of religious leaders were executed or sent to labor camps, where many perished. The purges created an atmosphere of fear and repression, making it nearly impossible for Muslims to practice their faith openly.

- Cultural and Linguistic Suppression

In addition to religious persecution, the Soviet regime sought to suppress the cultural and linguistic identity of the Muslim populations in Central Asia. The authorities implemented policies aimed at Russification, which involved the promotion of the Russian language and culture at the expense of local languages and traditions. The use of local languages in education, administration, and public life was discouraged or outright banned.

Traditional Islamic practices and customs were also targeted for suppression. Islamic holidays and rituals were banned, and the state sought to replace them with secular Soviet celebrations. The wearing of traditional Islamic attire was discouraged, and efforts were made to promote Soviet-style clothing and behavior.

- Resistance and Survival

Despite the relentless repression, the Muslim communities of Central Asia found ways to resist and preserve their faith and identity. Underground religious schools, known as hujras, continued to operate in secret, providing religious education to the next generation. Families played a crucial role in passing down religious knowledge and practices to their children, ensuring the survival of their faith.

Sufi brotherhoods, which had a long tradition in Central Asia, played a significant role in preserving Islamic spirituality and practices. These brotherhoods operated covertly, providing spiritual guidance and support to their members. The Sufi leaders, known as sheikhs, were often targeted by the Soviet authorities, but their networks proved resilient and adaptable.

- The Post-Stalin Era

The death of Stalin in 1953 and the subsequent period of de-Stalinization under Nikita Khrushchev brought some relief to the Muslim communities of Central Asia. The intensity of the anti-religious campaigns decreased, and there was a slight relaxation of the restrictions on religious practice. Some mosques were reopened, and limited religious activities were tolerated.

However, the fundamental policies of the Soviet regime regarding religion remained unchanged. The state continued to promote atheism and to control religious institutions through organizations such as the Spiritual Administration of the Muslims of Central Asia and Kazakhstan (SADUM). This organization was used by the Soviet authorities to monitor and regulate religious activities, ensuring that they conformed to the state’s interests.

- The Decline of Soviet Power and the Revival of Islam

The decline of Soviet power in the 1980s and the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 brought significant changes to the Muslim communities of Central Asia. The end of Soviet rule allowed for a revival of Islamic practice and identity. Mosques were reopened, religious education was reinstated, and Muslims were able to practice their faith more openly.

The newly independent states of Central Asia, while still maintaining a degree of control over religious activities, allowed for greater religious freedom compared to the Soviet era. Islamic organizations and movements re-emerged, and there was a renewed interest in Islamic scholarship and education.

The case of Tajikistan and its communist inspired secular approach

Raising from the ashes of Russin imperialism where they were brainwashed to be an ultra secular person to recognize their Islamic civilization was not an easy task. Let’s analyse the central tactics used in Tajikistan.

The government of Tajikistan, a country in Central Asia, has enacted various measures that have been interpreted by many as anti-Islamic or restrictive towards the practice of Islam. These measures are part of the government’s broader strategy to maintain secularism and control over religious practices, fearing that Islam could potentially foster extremism and undermine state authority. Below is an in-depth analysis of some of these rules and their implications.

a. Registration and Regulation of Religious Organizations

One of the primary ways the Tajik government exerts control over Islam is through the strict registration and regulation of religious organizations. All religious groups must register with the Committee on Religious Affairs (CRA), and unregistered religious activities are illegal. This registration process is rigorous and often excludes smaller or non-mainstream Islamic groups, effectively marginalizing them. The CRA monitors sermons, religious literature, and activities, ensuring they align with the government’s secular policies (HRW, 2019).

b. Control Over Religious Education

The government has imposed stringent regulations on religious education to ensure it aligns with secular and state-approved narratives. Islamic schools (madrasas) face tight restrictions, and many have been closed down over the years. Instead, the state promotes secular education and has incorporated strict oversight of religious content in public education. Any religious instruction must receive prior approval from the Ministry of Education and the CRA. This regulation aims to prevent the spread of extremist ideologies but has also limited the traditional and independent study of Islam (USCIRF, 2020).

c. Restrictions on Religious Attire

Tajikistan has implemented several regulations concerning Islamic dress codes, particularly targeting women. The government discourages the wearing of hijabs (headscarves) and has banned them in public buildings and government offices. Women wearing hijabs face social and administrative pressure, including denial of public services or entry into educational institutions. This measure is part of the government’s broader campaign to promote “national dress” and curb what it sees as foreign and extremist influences (RFE/RL, 2017).

d. Limitations on Religious Practices

The Tajik government has placed various limitations on religious practices, including restrictions on mosque attendance and the observance of religious holidays. For instance, mosque attendance is regulated, and minors are often prohibited from participating in religious activities, including prayers at mosques. Additionally, the government has sought to regulate and control the celebration of Islamic holidays such as Ramadan and Eid al-Fitr, sometimes imposing restrictions on public celebrations and gatherings (Amnesty International, 2018).

e. Suppression of Religious Leaders and Groups

Religious leaders and groups that are perceived as critical of the government or advocating for a political role for Islam have faced significant repression. The government has arrested and imprisoned many religious figures on charges of extremism, incitement, or anti-state activities. High-profile cases include the arrest of members of the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT), the country’s main opposition party with an Islamic orientation, which was banned in 2015. The suppression of the IRPT and other similar groups underscores the government’s intent to eliminate any potential political challenges from religious groups (Eurasianet, 2015).

f. Surveillance and Monitoring of Religious Activities

The Tajik government maintains extensive surveillance and monitoring of religious activities to preempt any potential threats to state security. The CRA, along with other state agencies, closely monitors sermons, religious gatherings, and private religious practices. This surveillance extends to religious publications, online content, and even private conversations, fostering an environment of fear and self-censorship among religious communities (HRW, 2016).

g. Legislative Measures and Policies

Several legislative measures have been enacted to institutionalize these restrictions on religious freedoms. The “Law on Freedom of Conscience and Religious Associations” imposes various constraints on religious expression, including the registration requirements, control over religious literature, and restrictions on religious education. Amendments to this law and related policies have progressively tightened state control over religious practices (OSCE, 2018).

h. Promotion of a Secular National Identity

The Tajik government has actively promoted a secular national identity, emphasizing cultural and historical elements over religious ones. This promotion includes the revival and celebration of pre-Islamic cultural symbols and practices, such as those related to the Persian heritage and the Zoroastrian tradition. The government argues that these measures are necessary to maintain social harmony and prevent the rise of religious extremism, but they often come at the expense of Islamic cultural and religious expressions (Radio Free Europe, 2017).

I. International Criticism and Human Rights Concerns

These restrictive measures have drawn international criticism from human rights organizations, which argue that they violate fundamental freedoms of religion and expression. Reports from organizations like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International highlight the repressive nature of Tajikistan’s policies and their adverse impact on the Muslim population. The United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) has also repeatedly placed Tajikistan on its list of countries of particular concern regarding religious freedom (HRW, 2019), (Amnesty International, 2018).

J. Impact on the Muslim Population

The cumulative impact of these policies on the Muslim population in Tajikistan has been significant. Many Muslims feel marginalized and oppressed by the government’s secular policies, which they see as an affront to their religious identity and practices. The restrictions on religious education, attire, and practices have disrupted traditional ways of life and created a sense of alienation among the faithful. Furthermore, the crackdown on religious leaders and groups has stifled dissent and limited the community’s ability to advocate for their rights (Eurasianet, 2015), (RFE/RL, 2017).

The current president for forever Emomali Rahmon who captured power in the 90’s and since then captured all the institutions and now runs Tajikistan as a family business. He sees Islam as a force that can overthrow his dominion and that’s why his brutal regime wants to control every aspect of Islamic life. So, the current ban we heard in the news is not new, we have seen such tactics used by the USSR/Russian imperialism. These are the same tactics that were used by Kama Ataturk in Turkey, in Azerbaijan which is now being used by China. The right wind Indian media and those dedicated websites want us to move in this direction. Their agenda is to repeat what has been done before.

We must understand that India is a unique country, and there is no other nation in modern times that can compete with its diversity and rich history of togetherness. Our founding fathers envisioned a secular nation where everyone can be represented and free to practice their beliefs. India has demonstrated to the world how people of different faiths can live side by side. We must preserve this version of India and not let the media destroy the basic fabric of our society.

Bibliography

- Human Rights Watch (HRW), 2019. “Tajikistan.” In World Report 2019. Available at: HRW

- United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), 2020. Annual Report 2020 – Tajikistan. Available at: USCIRF

- Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL), 2017. “Tajikistan Bans Hijabs In Public Buildings.” Available at: RFE/RL

- Amnesty International, 2018. “Tajikistan: Rampant religious freedom violations in the name of countering extremism.” Available at: Amnesty International

- Eurasianet, 2015. “Tajikistan Bans Main Opposition Party.” Available at: Eurasianet

- Human Rights Watch (HRW), 2016. “Tajikistan: Worst Religious Crackdown Since Soviet Era.” Available at: HRW

- Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), 2018. “Report on Freedom of Religion or Belief and Freedom of Assembly.” Available at: OSCE

- Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL), 2017. “Tajikistan’s Secular Identity Campaign Faces Resistance.” Available at: RFE/RL